There has been increasing interest and research in recent years into the science of wellbeing, resilience, stress and trauma. From the neuroscience of early attachments to new methods for healing trauma or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, we are gaining valuable insights into how we work as humans. This includes what a healthy human in a state of well-being is, how we respond when stressed, the processes that happen when we reach extreme states of threat, and the all-important question – when our capacity for coping in the moment is overwhelmed, what happens next?

This is one piece of writing in a series that aims to link together some of the big enquiries of my life:

- What are the patterns needed to create healthy human beings – not just people with good physical health, but healthy in body, mind, emotions and spirit? What is needed for people to form loving relationships and set appropriate boundaries, to contribute in good ways to society and help others to do the same; to create or support ways of living that are kind, sustainable, equitable and enjoyable

- What takes us out of health? Why do we have this capacity for creating unnecessary suffering for ourselves and each other, as well as such immense destruction of other life forms and the living system of which we are a part, and on which we depend?

- How can we bring together understandings from psychology, neuroscience, therapy, theories of power, privilege and oppression, to create cultural maps and insights that guide us in how to create the best possible circumstances for us to live well – not just for us, but for all life on earth?

In these times of growing crisis, how can we apply these understandings to deepen our personal practices, to build solid alliances, to stop using unhelpful frames and ways of seeing, and create groups and organisations that can challenge the forces of destruction, selfishness, greed and control that operate within and around us?

This is the first in a series of articles that explores:

- The journey of trauma for an individual – map of human nervous system states

- Health includes all the states, including the return path from freeze

- When we experience threat or overwhelm within a healthy culture there will be something in place to bring us out of freeze, and we can return to healthy functioning

- Trauma occurs when we cannot return from the emergency state and it continues to live in us, distorting our perception and behaviour from what is appropriate

Further articles will explore the extension of this into societal health and trauma, and resulting systems of partnership or dominator culture; the roots of oppression in this post-cultural trauma landscape, and what is needed to bring a culture that is pervaded with traumatised patterns and thinking back to health.

Health warning for readers!

There is a lot of writing about painful experiences in this article. I believe that most of us in the modern Western world carry some degree of trauma – from our personal upbringing, and as the result of living in a culture with a long history of oppression, both directed to those within our society and outwards through processes of colonisation and domination. When we read about trauma, it may bring our own experiences close to the surface, and leave us feeling disturbed in some way. If you haven’t already read the Core Concept on Trauma I encourage you to read this first, and to feel the impact this has on you – in your body, your thoughts, your feelings.

Within each of us who carries some trauma, we will have the three parts of our self that are identified in Franz Ruppert’s model. The trauma part is stuck in the moment of the trauma, frozen in time as if it were still happening. If this part surfaces, you may experience its feelings of helplessness, grief, isolation, despair, anxiety or fear. Its beliefs may surface – that there’s no point reaching out to others because no one will help you; that life is bleak or even unbearable; that these feelings are always with you and will never go away.

You may find that the survival parts surface. You might experience reactions to what I’m writing that are more charged than a simple disagreement would justify. You may want to stop reading because it’s all rubbish, because it’s boring, or nothing to do with your experience. This might take many forms!

The only part that can meet this information with equanimity is the healthy part of us – the part that knows there is trauma (in myself as well as out there); knows that there are survival parts trying to keep the old beliefs and behaviours going in ways that are out of date and probably unhelpful; and knows that there are now people who can offer support, and that there is love, ground, help, resources, understanding, and practices that can help any states of overwhelm to move through.

I invite you to pause as you read this and notice what is happening to you – body, feelings, mind? If you are starting to feel tense or agitated, try some of the practices listed here which may help you to release any tension or charge. [Capacitar link]

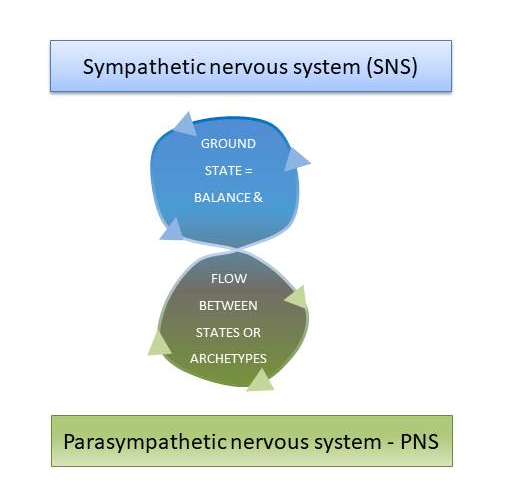

Ground state – relaxed flow

In our ground state, of open relaxation, humans move between activity and rest, between outward mobilisation and inward digestion and connection. At a physical level our autonomous nervous system is mediating these shifts. As our sleep ends, the sympathetic nervous system comes on line – waking us and increasing heart rate and blood flow to get us moving. When we move towards rest, the parasympathetic slows us down, increasing blood flow to the digestive system and reducing heart rate. Throughout the day we move between more or less activation and rest.

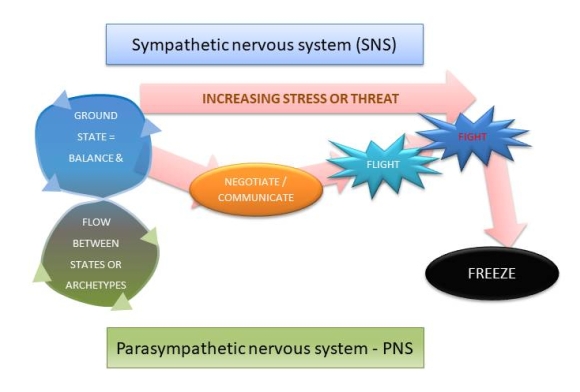

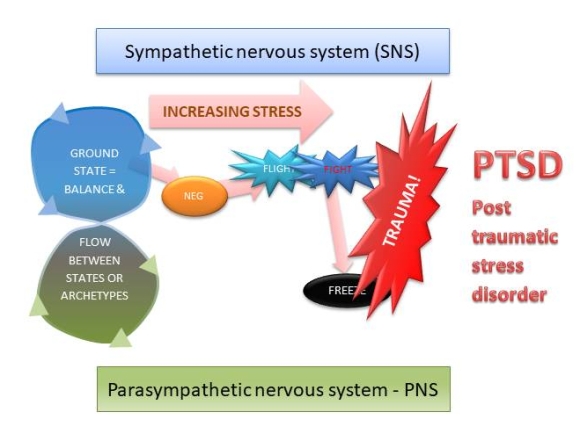

In healthy human cultures we may find simple daily rituals that help us with this – such as morning meetings to plan the day; warm ups and team talks before sporting events; evening storytelling, lullabies for babies, siestas after lunch and so on. Here’s what this might look like in diagram form:

Jon Young describes this kind of ground state for birds in his book “What the Robin knows”. It’s efficient in terms of energy. Much of life is lived here. Being attuned to the range of threats, and wired to respond appropriately even birds which are prey rather than predators will spend much of their time relaxed, going about the business of living – finding food, nesting, mating, raising young, perhaps even the joy of flying or singing.

I think it’s interesting to reflect how much time people living in modern society spend in either of these relaxed states. You might want to ask when you are truly in a relaxed doing mode, without pressure of time, or getting it right.. and similarly whether in your down time you can let go of pressure and just be with yourself or with others?

Stress States

As stress or threat increases the autonomous nervous system moves through the hierarchy of responses – sometimes in an instant, with the amygdala system sending the body directly to emergency flight / fight or freeze, and sometimes moving through the stages of communicate / negotiate first – then if that fails and stress escalates, moving to flight then fight, and if all else fails, freeze.

The threat may be physical, emotional, sexual, or something else. It may be an attack on our identity, being criticised by someone in a position of power, or shamed in front of people whose good opinion we depend on. It could be inappropriate or hurtful sexual interference or assault. It could be control through the experience or threat of physical or other forms of violence. And it can be a continual state of stress over time through constant pressure of deadlines, being undermined, a state of scarcity or insecurity, or excessive isolation.

We can also imagine or think up stressors – thinking about something stressful can have the same physiological effect as an actual event.

Our body / mind / nervous system has evolved this set of responses – partly through our evolution from reptiles to mammals to primates, each layer of evolution adding more complexity to our range of options. Reptiles only have the freeze option available. The mammalian brain adds flight / fight, and our frontal cortex adds the possibility of negotiating our way out.

All of these are healthy, natural responses that our body and nervous system is wired to activate to help keep us alive. Here they are added to the ground state diagram:

Stephen Porges’s Polyvagal theory proposes a more complex set of stress responses than the fight / flight / freeze that many of us are familiar with. These responses have evolved to ensure survival 1) by adopting an appropriate strategy to the level of threat, and 2) minimising energy use. They work in a hierarchy – the greater the threat the higher the level of response adopted.

I’ve described the hierarchy of stress states in more detail here. And summarised them in this table, relating the responses in terms of archetypes as well as physiological responses:

| What does this look like?

When did it evolve |

Body / nervous system response | |

|

GROUND STATE (free from threat) |

Action without stress – wake / work / play / make / do | Relaxed SNS – energy to muscles for work, play, dance |

| Rest, digest, connect, tell stories, sing, gentle play, soothing, sleep | Relaxed PNS – resting, soothing, energy to digestion, relating | |

| INCREASING LEVELS OF THREAT

ê

|

1: Communicate / negotiate

Activated and relating; there is a sense of stress, but not desperate Primate / social / frontal cortex response |

SNS and PNS: mobilise and inhibit

Focus on listening, awareness of other/s Energy to communicate through facial expression and voice |

| 2: Flight

Emergency action – mobilise to escape threat Mammalian response |

Emergency SNS: mobilise

Withdraw blood flow from digestion and non-essential activities. Adrenaline raises heartbeat, ready to escape and run |

|

| 3: Fight

Emergency action – fight to escape or overpower the other Mammalian response |

Emergency SNS: mobilise

As above but ready to fight not run |

|

| 4: Freeze

Emergency shut down – immobile and listening for opportunity to escape Reptilian response |

Emergency PNS: full inhibition

Full shut down. Numb pain. Inhibit muscles. |

If we add these states to the diagram of nervous system states, it looks like this:

Coming back from flight / fight / freeze

When we have been in a situation where we got to a full emergency arousal the important thing is what happens next.

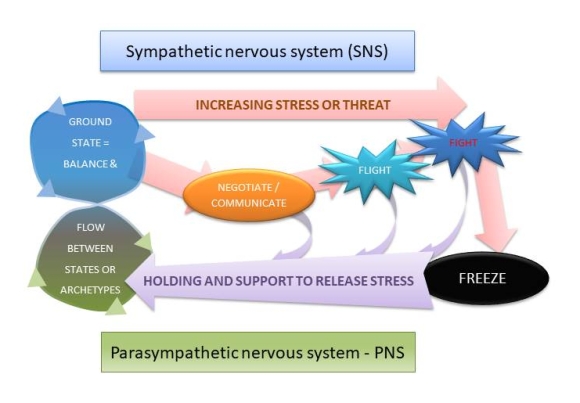

In a good situation there will be enough holding and support to fully recover and go on functioning as before. For those who reached flight or fight this may mean recounting the story, expressing any feelings that are left – such as fear, anger or hurt that were put aside to deal with the situation. This may also require that we physically move, releasing muscle tension and emotional holding in our bodies.

If we don’t get the support to process the stress of the situation we are likely to be left with a residual impact. If this is severe we start to enter into the landscape of trauma. One definition of trauma which I’ve found useful is exactly this – a negative experience which leaves lasting damage to the healthy functioning of a person (or other being) or group. You can find a definition and exploration of trauma here.

Peter Levine’s work shone new light in the west on the impact of stressful situations and how it is held in the body. Previous ways of working with trauma had focused on cognition and emotional components. His work brought to light the effect of reaching the freeze state, where a flight / fight arousal is overridden by the PNS and the body is shut down. He observed gazelles which had been caught by lions managing to escape by freezing and playing dead, so that the lion lost interest. Once the threat had passed he noticed the gazelles tremoring through their whole body. Then they would continue to graze, returning to their ground state.

His book “Waking the tiger” describes how found that a similar process is possible for humans, so that even long after an extreme threat in which we felt powerless, we still carry the energy of the arousal held in the body, and can discharge it with the right support and methods, leading to rapid healing from the trauma.

When I thought about this insight in relation to other human cultures I wondered whether they had equivalent techniques for healing people who had been in extreme situations. I was impressed when Rob Hopkins, a colleague in the Transition movement, told me about interviewing one of the grandmothers at Standing Rock. He asked what they did with people who had been on the front line of the protest, and subject to abuse or violence, committed to neither fighting nor fleeing. She said, “We take them to the sweat lodge”.

So this was one method for releasing stress from the body. I believe that the grief ceremonies of the Dagara people as shared by Sobonfu and Malidoma Some could serve a similar purpose – regular rituals for the whole village which involved drumming, dancing, and supported time at shrines for support and for full vocal and physical expression of anything that needs releasing. Similarly the Bushmen have “trance dances” and many tribal people have some kind of spiritual healing ceremony that creates holding, rhythm, movement and welcomes physical and emotional release.

If we add this return path to the map of escalating response it looks like this:

The return path is crucial for human well being

There isn’t anything wrong about any of these states or processes. Life brings stress and threat. Research shows that we need stress to develop – it’s absolutely not a bad thing. In some circumstances flight and fight can be enjoyable – think how many games children play are a version of going into these states, how many adult sports are ritualised forms for combat or outrunning your opponent. Life without any fear or threat becomes tame and stagnating.

And in whatever age of human history, whatever part of the planet we live on, there are real threats to our safety. Whether from conflict within our own groups, battles over territory, car crashes, unjust laws, sexual abuse or domestic violence, predating wild animals or a thousand other causes, humans have always faced physical and other threats to our lives, our safety or our sense of self as autonomous and empowered people.

This continuing capacity to return from stress states to this ground state of relaxed, relational, caring action and rest is a crucial determining factor of whether human beings can return to a state of relaxed open existence.

Trauma involves a failure of the holding field after the event

When I first started out as a psychotherapist and did a short stint of work in a centre for people who have experienced sexual abuse, I came across a powerful idea about trauma. It’s that trauma is not the incident of abuse (or other extreme stress inducing event). Trauma is that event plus the failure of the holding field afterwards. People who are sexually abused who feel safe enough to talk about it, who receive support, where power is brought to bear on the perpetrator so they cannot repeat the abuse, where the blame and shame are put where they belong, with the one committing the abuse and not the one receiving it, are far less likely to have long lasting impact from the event.

I read Peter Levine’s book “In an Unspoken Voice” and saw a similar message. He describes beautifully his experience of being hit by a car, and how the first intervention of a well meaning paramedic shouting alarmed instructions contributed to freezing his body in its shock response. A bit later a paediatrician came and offered a gentler response, which enabled him to start processing the physical shock as he connected with her touch and soothing voice as a resource, allowing him to find his own physical and emotional responses to the accident. He describes how this access to an external soothing and reassuring resource supported him to continue processing the shock through his system as he was taken in the ambulance, so that by the time he arrived at the hospital his body was pretty much back to normal. The ambulance crew were so astonished by his recovery they asked to be trained in his methods, and so started a whole programme of emergency Somatic Experience training for paramedics.

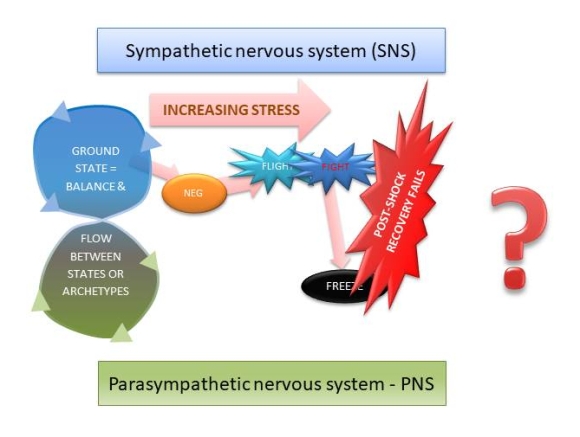

Here we start to reveal a hugely important loop about our culture. If we don’t understand the physical and emotional processes of shock and trauma, we don’t know how to respond when an individual undergoes a potentially traumatising event. So people who might recover quickly if supported are left with the impact continuing in their system. Here’s how this might be represented in diagram form:

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: the consequence of the loss of the return path

If we reach an extreme state of stress and there is no recovery there will be a lasting impact which will be physical, emotional and mental. This is the definition of trauma I use – an event from which we do not fully recover, which leaves lasting damage to our healthy functioning.

This state, where we experience something extreme and there is no recovery , and our physical and psychological response to it, is often referred to as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This recognises the causing event or situation as trauma, and recognises there is a disorder which continues after the event ends.

In recent years there has been increasing research into PTSD among soldiers returning from war. Symptoms include drug and alcohol abuse, flashbacks, suicide, violence towards loved ones and major depressions (e.g. see this report).

In these symptoms we can see the over-activation of the flight / fight / freeze response, as if the emergency situation is still present, which for the nervous system, it is.

- Flight: escape through drugs or alcohol; unstable lifestyles (many veterans end up homeless)

- Fight: reactivity and increased violence

- Freeze: despair and depression.

Here’s PTSD added to the model – now a new, enduring state on the other side of trauma.

I’m fascinated by the increasing interest in trauma as an underlying condition which impacts us both individually and collectively. And by the growth in methods discovered, or recovered, which are being used to heal trauma, more and more directly. I’ve listed some of the methods I’ve come across, or used myself, for working with trauma at the bottom of the trauma definition. These are modern, western methods to work with individual trauma.

Many human cultures have evolved processes for healing those with trauma. Whether there was a conscious understanding of trauma as a psycho-physiological condition, whether it was seen as a spiritual crisis or sickness, or something else, cultures throughout time have discovered or created ways of getting people back from a state of shock or freeze.

For an individual, this return path can fail, and there may still be opportunities for healing later. But that’s assuming that the culture in which the individual lives has functioning practices for the return path.

In the next article I’m going to explore what happens when a whole society is traumatised – for example by famine, war, colonisation, or other extreme, widespread or ongoing circumstances which leads not only to widespread shock, but to the loss of the people who hold the healing practices – the elders, shamans, healers, carriers of the ceremony or whatever..