This blog post was originally written for Transition Network. A version was delivered as a webinar for Transition US in 2014 (you can still hear the original talk here). I’ve included it because these stories are still present in our everyday media, and I think it’s helpful to lay them out even when the landscape has changed significantly.

What stories are we telling ourselves about the future? What choices do we have? What’s going on underneath the stories we tell, and how can we use them to help gain clarity about where we are and where we’re going?

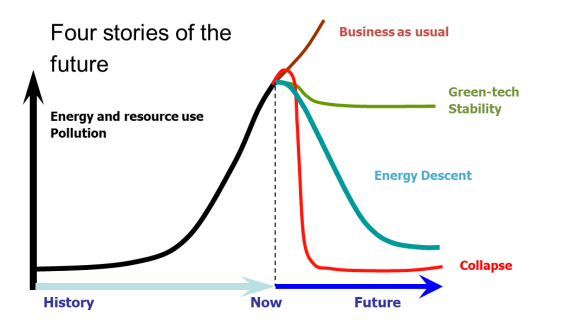

The ideas shared here originate in a session on Vision in the Transition: Launch training which borrowed from the permaculture teacher David Holmgren’s book, Future Scenarios. It looks at the four main stories that are widely present in mainstream media, at the psychological processes that can be seen running underneath them. It explores the challenge of having so many contradictory stories present simultaneously. And it looks at which are actually possible, or likely, and how to distinguish between technologies that take us in the right direction, ones which create more disastrous futures, and those which sound good but are actually wasteful dead ends.

Just a note on the graph: up till now all the elements on the vertical axis have grown together – resource and energy use and pollution. Sometimes we’ve included population on this axis. Whether these four things will continue to be linked is a profound question, one that no one actually knows the answer to. The second half of the graph really shows resource and energy use – and therefore most probably pollution. Whether there will be a corresponding fall in population is a hot topic – but not for here.

What are the four stories?

Business as usual

This is the story of continued material growth. Every problem has a technical solution. Because we have always found a way out of every difficulty we will always be able to do the same. Limited resources or ceilings on pollution levels do not apply to the human species. We can go on growing our population, material wealth, energy demand, and waste output for ever.

Collapse

At the other extreme, we carry on attempting to grow and hit a catastrophe – runaway climate change; sudden collapse of a global systems for food and other life essentials entirely dependent on cheap energy; nuclear or other wars over scarce resources. (There are other scenarios less related to the predicament we have made for ourselves – comets, reversal of the earth’s poles, unstoppable illnesses and so on). Population and technology use crashes. A much smaller population lives on in the ruins of our civilisation.

Green stability

In this story we have the same lifestyle but we make green versions of everything we have now. Electric cars, high speed trains, super insulated houses, lots of renewable energy. Overall we aren’t growing, but we also don’t have to reduce anything much. This story is popular with business and politicians – it suggests there might not be too much material discomfort as we deal with the changes that are needed.

Energy descent

In this story our use of energy and other resources – and hence pollution – follow the curve of useable energy, falling rapidly over the next decades. We use all the intelligence, creativity and collective human effort it took to get up the curve so quickly to descend gracefully.

How does identifying these stories help?

In 2009 I was one of three Transition trainers who ran a workshop for local authority staff in Scotland. We used these stories as a way of talking about the future, and the assumptions that underlay their work. We found that they were required to assume at least three of these stories regularly (all except Transition / Energy Descent) without noticing that the assumptions were wildly contradictory. (E.g. flood defences for low lying coastal villages – collapse; electric vehicles for the car fleet – green tech; new business parks – growth).

What is the effect on our psychology when we are working in different stories, simultaneously, and unconsciously? The same happens to all of us when we engage with the media – there is no explicit statement of the assumptions underneath the content. I see that the effect of this is a kind of bamboozling – that our brain simply shuts down trying to find a coherent position, and gets used to working in several realities at once. I saw in the workshop that once the stories had been named and explored the council staff had more psychological ground.

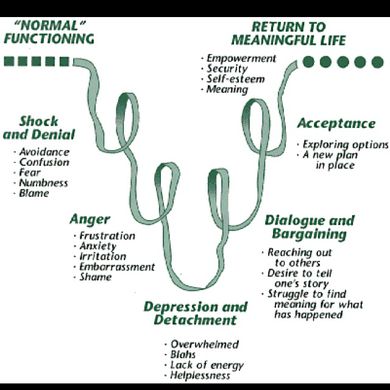

There are other ways these stories can help us see more of what is going on for us when we think about the future. Applying ideas from two different psychological fields helps us deepen our understanding of the stories and their significance. One is to recognise the trap that addicts are caught in. The second has to do with understanding responses to unwanted change – usually from the field of bereavement.

Growth or Collapse? The place of addicts

When we were doing research into future stories for Transition Training we noticed that these are the only two futures that any film has depicted, as well as almost every book written about the future. Often the future is both brutal in some way and technologically fantastical – with flying cars, huge populations and metropolises and so on. There are increasing numbers of sifi films about global disasters, from The Day after Tomorrow to The Age of Stupid.

I noticed that this is a similar way of thinking to the belief structure of an addict: “Only my ‘fix’ makes life manageable..

It’s worth noting that politicians are caught in a trap of maintaining the story of business as usual – because it would probably be electoral suicide to be the first party to announce that growth is at an end (even though many politicians increasingly acknowledge this privately).

So one of our key tasks in this time is to imagine for ourselves what a desirable future would look like which is neither a techno-fantasy world of every increasing growth, nor a disaster scenario – because our politicians and media generally aren’t doing it for us.

Stages of Change and Loss

These four stories of the future have a deep resonance in our psyche because they relate directly to the phases that we go through when are faced with a loss that is outside our control. The model is described by Elizabeth Kubler Ross in the process of bereavement, or a diagnosis of terminal illness. In her model there are five phases, which go something like this:

Shock and Denial

“It can’t happen to me, things will go on as before”. As in the Business as Usual story the person clings to a belief that a solution will be found, despite mounting evidence to the contrary, both from experts and personal experience.

Destructive rage, despair

The Collapse story of the future is paralleled by destructive behaviour to self or others “I’m going to die anyway so I may as well keep drinking / take risks with my health / take it out on others”. Another similar response is despair, sinking into depression and apathy, refusing to engage with what is left of life. A commonly expressed version (which doesn’t sound angry, but implies an appalling refusal to engage with the suffering it proposes) is the version that says something like “it’ll be a good thing if humans are wiped off the face of the earth, we have caused so many problems, we are like a cancer on the face of the planet”.

Bargaining

In this phase we make deals – “If I eat well, or pray every day, or am really good, I’ll be allowed to live”. The equivalent in our stories is that those in power, with wealth and privilege, believe they can keep their lifestyle if it’s made green. Another really common version is that we give up one thing but keep another. “I’ll stop eating meat but still fly for my holiday every year.”

Acceptance

In the Energy Descent scenario we accept that the Earth places limits on all life forms including us and acknowledge that life can be worthwhile and meaningful without high material consumption. Our resource use and pollution, including Carbon emissions, must fall continually in future years and our only choice is how we deal with that. What happens as we come down the energy curve is a huge question – do a reducing number of rich and powerful people hold on to everything they can while the rest of the world is increasingly impoverished (the Austerity story in the UK)? Do the rich accept that they are the ones whose lives most need to change, and start to engage with the task? Do communities come together to re-imagine and rebuild their way of life as resilient, relocalised community economies (Transition)?

It’s helpful to use models of loss in the process of coming to terms with information about the changes needed to affluent lifestyles in our time – another example of this is Rosemary Randall who set up the Carbon Conversations project which uses models of loss such as Worden’s “Tasks of Mourning” to help people through the change process. Understanding the processes and support which help us to move through the stages means we can design support, training and interventions for ourselves and others. Some of the tasks will include things like:

- Getting to grips with the information, digesting and making meaning out of it – “What does this mean for my life, for my children’s future? Is my work still relevant? Should we move? ”

- Expressing feelings of grief, fear, anger, betrayal, uncertainty, despair, confusion, and so on. Processing the feelings that naturally arise from the diagnosis is a necessary part of getting to a place of peace.

- Establishing a new sense of identity – which could include losing relationships, making new ones, changing what we eat, wear, how or where we live and so on.

It’s also worth noticing that the models of loss generally relate to something that is dear to us, a loved one departed, a terminal diagnosis of our own life. In some ways this is true – many things of great value and benefit have come from the high tech modern lifestyle. But it has also brought high levels of loneliness, anxiety and depression, destruction of indigenous peoples, natural habitats, species extinction, pollution and resulting sickness and so on. This brings us back to the addictions model. Are we giving up something beloved or a self harming addiction we’ll be better off without? (I think both are partly true.)

Which are possible and which do we want?

A key question arises from looking at these four stories of the future – what choice do we have? Once we look at the full picture of resource and waste limits we can see that Business as Usual simply isn’t an option. The most deceptive of these solve solutions in one area by creating other problems in another sphere. So there are “solutions” to climate change that require massive energy infrastructure – ignoring carbon emissions and energy and other resource limits. Similarly tar sands, liquids from coal, fracking, ethanol, and other technologies might help to solve the energy crisis, but they have devastating environmental impacts, and don’t take into account increasing pressures on land and water for food supply.

If we refuse to engage with all the issues and attempt to keep growing we are most likely to end up with the Collapse scenario. We continue to use up our last easily available fossil fuels, we continue to burn coal and gas, we fail to address major issues of water supply, deforestation and so on – and future generations are left to deal with a degraded, asset stripped world, with extreme climate events if not runaway climate change, possibly large quantities of toxic nuclear or other waste with very few resources and a large population.

The last two stories – Energy Descent and Green Stability are the most difficult to distinguish, but it is important that we continue the attempt to do so. If we see ourselves nearing the end of abundant resources – energy, minerals, forests, fertile land – we have a limited window to put in place technologies that will genuinely see us and future generations into a liveable, sustainable future. The question of whether a solution belongs in the trap of “Green Stability” or “Energy Descent” is best thought of in terms of how far down the curve of reducing resource use it takes us, and how many people can benefit from it.

The first issue – how far down the curve does it take us – can be thought of like this. Does it reduce energy / resource use / waste not just by 10% but by a factor of 10, more like 90%? Increasing the miles per gallon of a car by 10% is useless when private cars overall deliver less than 1% efficiency. Switching from landfill to incinerating rubbish may seem like a solution to a pressing problem, but not when we consider that in the future we will be looking to get to almost zero waste – and what is now rubbish is increasingly being recognised as valuable source material. So the first criteria is to look not a few years ahead but decades ahead – and to put in place long term super-low energy systems.

The second issue is around who can access it. It’s becoming increasingly clear that not only is there a moral imperative to stop investing in technologies that benefit only a fraction of the global population, the structures which have allowed the wealthy of a few countries to enjoy material comforts way beyond that of the vast majority are in some ways being dismantled. As China and India and other countries gain in economic and political power many within their populations expect, and are living, the lifestyle of the affluent west. This despite the fact that the planet cannot possibly afford private cars, air travel, meat and dairy based diets and so on, for another two billion people. As we see inequalities within countries increasing many can feel the ethical and social unacceptability of this direction. It’s morally indefensible, and in time is likely to lead to riots and increasingly violent repression in order to stop those that are poor or even starving attempting to get what they need.

So solutions that will be peaceful and sustainable require criteria that they serve the vast majority rather than the minority.

We are living all four stories at once

In 2009 Transition Training did some work with local authorities where we used these four scenarios as a way to talk about the future. We asked officers and elected representatives to see if the stories applied:

- In requirements that were placed on them – by the electorate or by performance indicators.

- In changes they were planning.

- In how they viewed the future.

What we found was that in most departments all four stories applied to some of what they did. They were planning flood defences for villages affected by rising sea levels; reducing waste collections to save fuel servicing remote villages; business parks to spark economic growth, and support for renewable energy projects. The story that was most missing – which is often the case – is the Energy Descent story, the one we most urgently need.

We have also used the four stories as a personal reflection, to notice that as individuals we are often living all four stories at once. For example, I’ve given up my car (Energy Descent) and take high speed trains instead of flying for my holiday (Green stability?) but still eating meat, chocolate (Business as usual) and psychologically ‘spending time’ in despair and hopelessness (Collapse).

Acknowledging the enormity and complexity of the change process we are all in can help us to be less judgemental of other behaviours – of institutions and people who we might see as being less far along the change pathway than we are!

[There is also a draft version of a game where players are dealt a number of cards suggesting current and possible future technologies, with the invitation to place them in one of the four scenarios. The trickiest are Energy Descent vs Green Stability – and for some I believe it’s impossible to say which combinations of solutions will actually endure.. if you’re interested to get hold of this let me know].

Conclusion

I hope this post gives some useful insights into the stories that are current, and ways they can help us to deal with the process of change we are all a part of. Many I’ve spoken with have found it relieving to have the stories framed in this way – that rather than seeing them as competing narratives they all form part of one process of digesting and coming to terms with the enormous shifts in understanding we are going through. Seeing them together helps us to regain a sense of ground – where in many organisations and conversations the assumptions switch from one story to another without naming what’s happening – as we found in the local authorities. And having tools which help us distinguish one from another is also vital to support good decisions for where to put our energy and resources.

If you haven’t done anything like it I’d encourage you (maybe with others if you are part of a group in Transition or something similar) to think about how you are living all four stories in your own life. I believe it’s inevitable that we are part of Business as Usual in some way – though that may feel uncomfortable. We need to give space to the places where stories of Collapse or despair arise, and allow the feelings of grief and helplessness of rage and uncertainty to have their place – or they will come into our meetings as frustration, judgements, relentless driving ourselves or exhaustion. It’s healthy to see where we’re bargaining with the future, not yet ready to let go. And it’s good to recognise how far we’ve come – and celebrate the changes we’ve made, without making that something to judge others with because their path is different.

I’m not suggesting I manage all these things by the way – for me navigating the complexity of this journey is part of the endless, challenging, impossible and just-doing-my-best nature of our times.